| Date | Author |

|---|---|

| 15th November 2022 | Tom Owen-Smith |

Let’s imagine you have just completed your new strategy. You have launched it with a splash, and your staff and students have been energised by their opportunity to contribute what the university will look like in five, ten or however many years’ time.

It’s a truism to say that doing the thinking is the easy part. But moving your strategy from paper into reality is complex and calls for coordination of resources across your institution. In the second of two posts on institutional strategy, SUMS Consultant Tom Owen-Smith considers some of the elements that play a key role in successful strategy delivery.

This is not an absolutely precise science and conditions will always vary between organisations, but getting these elements running well, and crucially in harmony, will set you in a good position to realise the ambitions of your strategy.

Balancing Transformation and Business as Usual

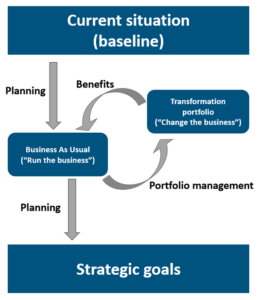

The key to successful delivery of your strategy is balancing and coordinating the roles of your so-called “Business As Usual” or “BAU” on the one hand and transformation on the other. The phrase “run the business, change the business” captures this well.

BAU refers to the perennial activities which make up much of the core business of universities in teaching, research, external impact etc. While BAU forms the bulk of work at your institution, it’s likely that your strategy will include at least a couple of major projects or transformative initiatives.

These run on a different timeframe and cycle from BAU. BAU is constant while transformation initiatives have a beginning and end. BAU tends to run on planning and budgeting cycles, while transformation initiatives might be conceived end-to-end over longer periods, particularly capital projects.

But although BAU is cyclical, it is constantly evolving. Part of that evolution is due to the changing nature of core business itself, and part of it is stimulated by transformation initiatives, which deliver planned and measurable changes or “benefits” to your BAU operations.

Business As Usual: Planning, Timescales and Targets

The perennial question arises: how far ahead and in how much detail do you plan? The answer (frustratingly!) depends on your operating conditions, the nature of your goals, and how your institution is set up to deliver them. That said, there are some rules of thumb which serve as a good guide to effective planning.

Firstly, your institutional strategy should have some quantitative dimensions, however impressionistic these may be. The longer your strategy is expected to last, the more indicative or “ballpark” these figures will be, but some quantification starting out from your current baseline allows you to set and track your course towards where you want to be going.

How might you achieve this? When putting together your strategy, you may have already moved into doing significant thinking about how you will deliver it and included some of this in the strategy itself. This may already include some expression of quantitative aims (perhaps referred to as “targets” or “key performance indicators/KPIs”) for the institution.

If not, when you come to planning your strategy delivery in more detail, it can be useful to buttress your qualitative strategy with a quantitative strategic plan at the institutional level, which sets broad quantified endpoint targets for the most important themes in your strategy and incremental steps, usually annually, indicating in rough terms the track to getting there. Targets should have a senior owner who oversees progress towards them, and who is responsible for explaining the reason (and there may be a good reason) why, if they are not met. Elements such as student size & shape and research objectives are particularly important here, as they will determine key resource needs such as workforce, space and core systems.

Secondly, just as your strategy reflects the things which are most important to your institution, your targets should reflect the things that you most need to measure and which best demonstrate whether you are progressing towards achieving your aims. On that note, you want to keep the efficacy of the measures themselves under review, as sometimes a desire to measure up well can encourage gaming behaviours.

As universities do many things and have multiple drivers of success, many institutions adopt a balanced scorecard approach, which evaluates performance across a range of indicators covering finances, resource profiles and importantly the impacts achieved through education, research and other activities.

The way you use and structure your data is crucial here. Although you will likely have multiple indicators for your key themes, you should be clear about hierarchy and which indicators are the most important. You should also be specific about whether targets are for the whole university or specific levels or parts of it, and whether certain divisions have bespoke indicators on their local balanced scorecard. Remember also that some measures are unavoidably retrospective or “lagging”, and some things (research impact, graduate outcomes, civic engagement, to name a few) are hard or impossible to measure in wholly quantitative terms!

Thirdly, your targets should be developed and managed as a coherent set, which recognises their holistic nature and the dependencies between them. Universities’ business models are based on heterogeneous activities with different profiles around income and costs, and usually a degree of cross-subsidy.

Targets can be changed (especially if you refresh or adjust the course of your strategy), but it’s important to remember that resources (money, time, organisational energy) are necessarily finite. Consequently, trade-offs come into play and moving some targets may likely affect others. To take a couple of examples, an aspiration to do more research (which is expensive and tends to be cross-subsidised) may entail increasing other income sources to pay for it; or while decreasing your targets for postgraduate students in a certain department is likely to mean that you generate less margin, it might allow you to focus more closely on undergraduate success.

Fourthly, your targets and your progress towards them should be reviewed and controlled through your planning and budgeting processes. Ideally this will be done annually with a three to five-year planning horizon, although shorter horizons are also used in some institutions.

A good planning process should take account of many similar points that you looked at more intensively when you were developing your strategy: the operating environment, developments and trends which are likely to bolster or hinder your ability to pursue your objectives, and an appraisal of risk aligned to an institutional risk register.

The planning process is also the key point at which trade-offs are managed and potentially the course is changed. As noted in the first part of this series, strategies should include mechanisms allowing for approach to be refined over time or perhaps fundamentally rethought. The environmental and performance data you collect for your planning process will provide the evidence you need to assess whether a rethink might be needed.

This echoes through to your people. The planning process should link to your annual appraisal and objective-setting process, and objectives or targets at different levels of the institution should be owned by the leadership at that level, whose responsibility it is to ensure that they are managed appropriately through the line. Also around the people space, your planning parameters should include considered workforce planning grounded in an operating model appropriate to your institution.

The Place of Transformation

So, your institution is always managing incremental changes through target-setting and planning in Business As Usual. At the same time, any organisation is likely to have a range of transformation initiatives underway, from small projects managed locally to large, expensive projects and complex programmes (a programme is a collection of related and aligned projects).

Some of your projects and programmes (generally the smaller ones, with or without discrete budgets) will typically be managed by your operational managers and their staff, while some will likely be big and important enough that they are managed by dedicated project managers. Capital projects spring to mind, but a wide range of other change projects could fall in this category. These large initiatives with formal structures are where the role of operational managers as sponsors (leading, shaping and being accountable for outputs/outcomes rather than delivering them themselves) comes into its own.

Important initiatives, those above a certain threshold of size, budget or strategic value (the criteria can be tailored) are best governed through an institution-level transformation portfolio. A portfolio approach enhances delivery by enabling systematic, institution-wide coordination of your major initiatives, including dependencies and resourcing. It also ensures that benefits from transformation initiatives are most effectively realised and made use of in BAU by making it clear when and where they will come onstream. This information is hugely valuable for the planning processes discussed above.

Budgeting and resource allocation can also be deployed to maximise the impact of a portfolio approach. Even in transformation portfolios, the budgets for transformation initiatives are often run through the business unit which is judged to have the strongest link with the initiative. Perhaps it is where the greatest benefits are anticipated, prepared the business case, or is providing most of the resource for the initiative. While this seems sensible for smaller initiatives where the resources and stakes are relatively low, for initiatives which are important enough to be in the portfolio there is a strong case for allocating funds through a discrete, central budget stream which is subject to more rigorous governance than smaller initiatives run locally.

Apart from allowing for better financial control over expensive initiatives, consolidating your budget for major initiatives, including capital projects, will clearly delineate the envelope your institution can afford to invest in transformation. This clarity, combined with portfolio-based techniques for scoring and assessment, will help ensure that your scarce resources are used for those initiatives that will make the greatest contribution to your strategic goals (in other words, “the right” initiatives). It also allows you to identify and wind down ill-aligned or legacy initiatives.

Naming this funding stream (“Strategic Investment Fund”, “Strategic Initiatives Fund” or similar) can further support this model by reminding colleagues that the envelope is finite, that investment decisions will be prioritised against other initiatives according to a clear set of criteria, and that they will be governed by a different set of rules from smaller initiatives run through BAU.

In many ways, a discrete budget stream for transformation is like a part of your overall resource allocation model (or “RAM”, the mechanism by which you attribute direct income and expenditure, allocate indirect income and expenditure, and set targets for the various parts of your institution), as it makes transparent the contribution of transformation initiatives towards Business As Usual and realising your strategic goals.

A Word on Governance

Your governance and accountability structures can also make a big difference to your ability to turn goals into reality. Just as engaged and energetic sponsorship is the key determinant of the success of transformative initiatives, the same applies with goals that you’re pursuing through BAU. If something is an institutional priority, it should have a named member of the leadership team who is accountable for seeing that it happens, or can justifiably explain the reason why if it doesn’t.

How Can an External Partner Help You Achieve Your Strategy Goals?

To repeat an earlier point, strategy delivery is complex and requires coordination across your whole institution. With the many cogs constantly turning, it can be challenging to step back and consider the whole machinery, how the parts are working together and what they are aiming at.

SUMS Consultants can work with you to align your energies towards achieving what is most important to you. We bring experience of enabling strategy delivery with universities of all shapes, sizes and colours. Our knowledge base covers not just a range of institutions, but the strategic and operational landscape of the higher education sector as a whole; and our membership model supports deep relationships, allowing us to convene cross-sector engagement on a range of questions.

Our consulting teams combine this deep knowledge of HE with senior level experience from other sectors, including global commercial consultancies, retail and other complex sectors such as the NHS and local government. This ensures that we retain our USP as a not-for-profit consultancy that truly understands the nuances of the HE sector, while allowing us to identify the latest knowledge and innovation from outside the sector in the UK and internationally, and deploy it for the benefit of our clients.

If you’d like to know more about SUMS services in strategy, planning and transformation portfolios, more information is available on the services pages of our website.

We’re also happy to discuss any topics raised here and what they could mean for you in more detail, free of charge. Contact Tom Owen-Smith at t.owen-smith@reading.ac.uk for more information.